Songs of the Week 01/20/2023

It's been a journey. I think I had two (unrelated) breakdowns over the course of writing this one. Only the spiciest posts for my most loyalest parasocial Toddlings.

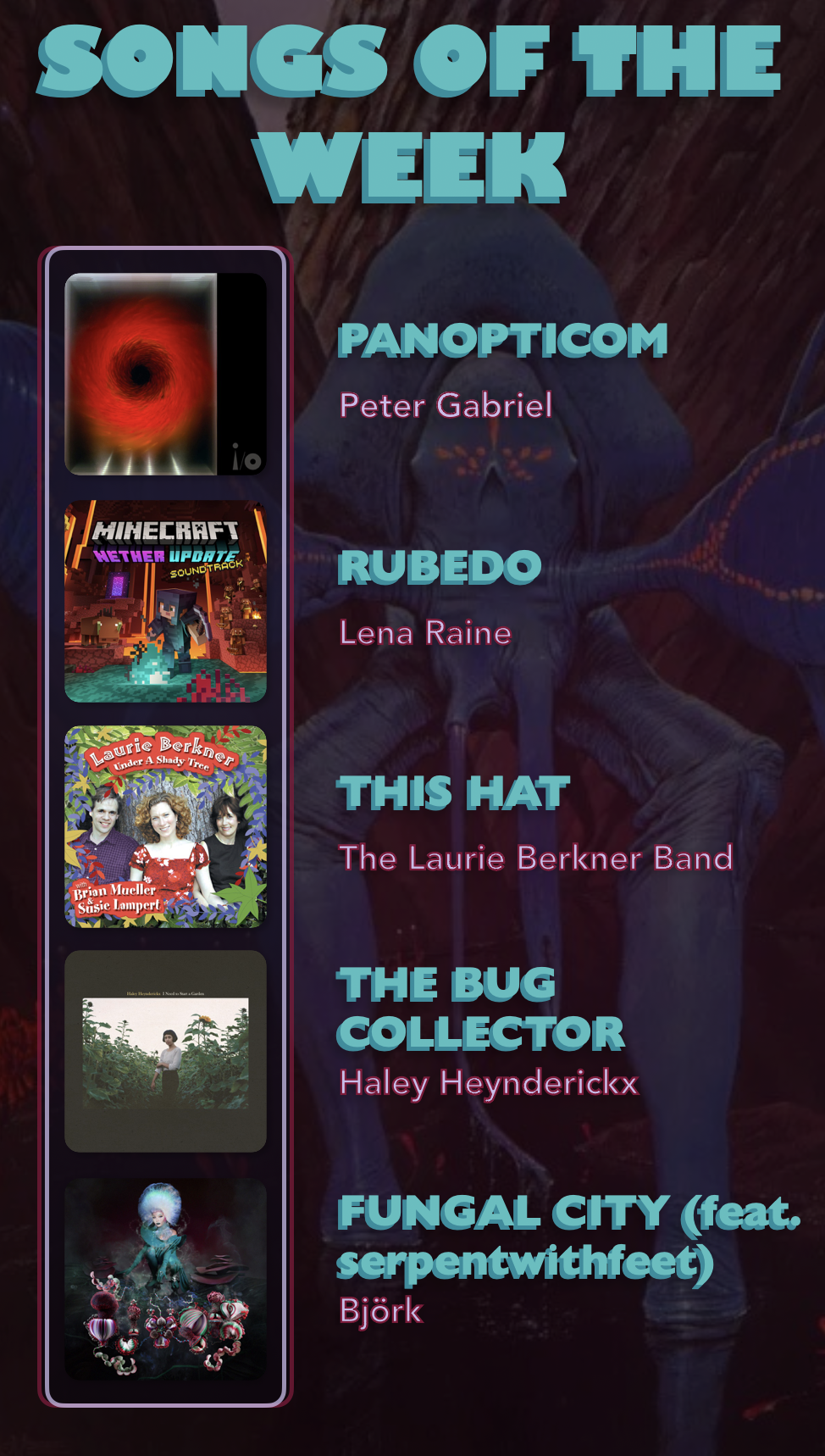

PANOPTICOM | Peter Gabriel Speak of the devil, and he shall appear... about six months later. I know writing, composing, arranging, recording, and distributing an album can be an arduous process, even for the masters, so I'm sending out my sincerest thank you to Peter Gabriel for being such a regular reader of Max Todd Dot Com and releasing new music just for me. He even made it about my internet addiction! Wow, um, called out! You really didn't have to say that in front of the world, God, and everyone, Pete, Petey, Pee-Gabe. I guess we're all just lucky to hear new music. Having been a game-changer in the music industry since the onset of the '70s, it's really a miracle that Peter Gabriel remains not only an innovative artist, but also an unwavering vocal presence. This won't be the last time aging musicians and their talents come up today, but I figure it's worth saying that, much as I love hearing vocalists age into new ranges and sounds, Peter Gabriel sounds essentially unchanged to me, something even the best 72-year-old musicians can't say. Being the ageless icon he is, I wouldn't blame Gabriel for a second if he chose to creatively coast on this image and rehash the highs of his career—sellout or not, the performances would be amazing. Yet here we are, blessed with not only a new tour at 72, but an album to go along with it, dropping a song every full moon, no less. While "Panopticom," the first of these new tracks, doesn't strike me as the most innovative thing Gabriel has released, I was immediately struck by how odd it is even so. Though I'd like to take this song on its own terms, it's hard not to view these five minutes as a tour through Gabriel's career. The twinkling, tingling synth chirps and distant background cries frankly reek of Peter Gabriel 1-4 and the earlier, eerier years, while the more upbeat chorus has the accessibility and strong vocal focus of later years, like Us. From its play on Foucault's panopticon in relation to internet surveillance to its lunar single releases, I have a feeling we're in for another deeply psychological and conceptual treat. Seriously this time: thanks again, Peter Gabriel.

RUBEDO | Lena Raine Remember in Fargo, when...

https://www.youtube.com/embed/OQt9l34MVug

If you don't, that fifteen-pixel clip probably didn't jog your memory, but Colorado Januaries have a magical knack for unlocking this very rage in me without having the added stressor of hiring two hitmen to kidnap my own wife so I can get her rich, bloated father's millions via ransom (meditating usually flushes those thoughts out). I've said it before and I'll say it again: I loved winter until I started driving. As my lovely and wonderful girlfriend is eager to remind me, my snow angst usually comes out through whatever moody soundtrack I'm brooding to between shanking the driveway with a chipped yellow shovel. I find Wojciech Kilar's bombastically gothic, macabre, and painfully tragic soundtrack for Bram Stoker's Dracula is the closest music comes to the feeling of having cold ankles for half an hour on a Saturday morning. Recently, though, I decided to switch things up. Now, I confront the bleak desolation of mild back pain and stiff fingers with the much more pensive and atmospheric musical landscape created for Minecraft's recent Nether Update by composer Lena Raine. Cute, right? Not at all. Horribly evocative of hell and damnation. And very mature.

C418's original Minecraft soundtrack is practically generation-defining for a legion of chronically online zoomers (myself included)—you can't scroll two videos without hearing "Sweden" or "Wet Hands." Fascinatingly, though, I'm not sure many outside of that demographic associate any music with Minecraft at all (perhaps other than some parents who endured the era of truly awful song parodies that nearly killed the game). Even with the ungodly amount of playtime I've accumulated, I wasn't actually exposed to the game's score through the iconic C418, but instead by the game's new primary composer, Lena Raine. In retrospect, I can see why some were upset at C418's departure beyond blind nostalgia (something I'm never, ever prone to)—his usage of eclectic orchestration, such as the handpan, kalimba, and mellotron, were meant to evoke the sort of music residents of the game itself might make, and these unconventional and imaginative compositions feel just as much alien, enigmatic, and at times unsettling as they are whimsical and warm. Needless to say, Raine had big, seven-toed shoes to fill, and I don't envy her position. While I've found the Minecraft music she's since composed to be hit-or-miss, for me, her initial contributions in the Nether Update became instant classics. While they don't have the same almost unreadable quirkiness of C418's original score, they certainly don't drop the ball in conveying an otherworldly air of mystery, both conceptually and musically. While the Nether dimension in Minecraft somewhat resembles a hellish underworld, its 1:8 scale and oddly prevalent pig-based fauna suggest it's something much more alien, and Raine's all-too-short contributions highlight both aspects masterfully. Today's pick, "Rubedo," blends the supernatural with the plainly absurd effortlessly, lending the music an almost religious climax that gives me chills every time. Like the prior track "Chrysopoeia," "Rubedo" borrows its name from alchemical jargon, specifically pertaining to the transformation of lead into gold (literally and metaphorically) using the philosopher's stone. "Rubedo," or "the red" of the body, draws a rather insightful parallel to not only the nether's (I think unintentional) red, fleshy substrate and the gold that can be mined from it, but also the idea that this wasteland can (and has) been warped into something holier. "Esoteric" is a great descriptor for "Rubedo"'s sound on top of its story, with its backing melody played on an out-of-tune piano that adds an anachronistic element of human antiquity into this land of churning lava and rumbling undead. There's an almost tragic serenity in the build of this song, like any wide, panning shot of a volcanic wasteland should be. Unlike C418's nether songs like the equally excellent "Concrete Halls," there's nothing sinister or even ominous about "Rubedo"—like the most stirring of apocalypses, it simply feels broken. As the song builds to a sweeping, synth roar, there remains nothing malevolent about it; every time, I feel as though I've witnessed a force of nature, like a torrent of wind ricocheting through a yawning cave, layering an echo so colossal it's sublime. Or maybe I'm just pontificating about a kid's game.

I've already said way more than I planned about this one, so thanks for sticking with me through it. If I'm gonna squeeze all I can out of this, though, it's pretty cool to see the way that the community embraced new additions after the departure of a beloved composer. I'm particularly fascinated by the subtleties different people take away from the strange tone of these four songs—for example, there's a pretty awesome metal cover by RichaadEB that really leans into the percolating darkness in the background. That doesn't count as a separate recommendation, though, got it? Okay. Now that I've cheated the system, I'm gonna slap you again. Ready? I'm already winding up...

THIS HAT | The Laurie Berkner Band You want to talk percolating darkness? Sorry, mastery? Then look no further than the elegant virulence of The Laurie Berkner Band's "This Hat." Though unable to ride the indie airwaves, The Laurie Berkner Band instead found purchase in the underground scene through indie labels like Jack's Big Music Show llc., something of an Alan Freed for the new millennium. Though overlooked in comparison to other female singer-songwriters on the scene, Berkner's vocals distill the best of the powerful yet honest 90s. From the outset, she boils off the accumulated Suzanne Vega-esque literary intellectualism in favor of lyrics that cut straight to the heart of issues young millennials were clamoring to address. What kind of hat do we have? A magic hat. How does it fit? Perfectly. And, should we put it upon our collective heads, what might we be? Well, according to Berkner's insightful simplicity, we might possess the power to be just about anything. Though the footsteps of a financial crisis of proportions not seen in a century boomed over the horizon, Laurie Berkner stepped defiantly forward to tell listeners that any hat, every hat, could fit perfectly upon their heads—that, in the face of an imminent capitalist culling, each and every human life has a place in this world; a hat in the ring.

Okay, I don't like this anymore, Laurie Berkner deserves none of my attitude. You know what I do like? That strange, descending harmony in the chorus for "this hat is my hat / I wear it all the time." You know what else I like? That little horn ditty at the end of the Under A Shady Tree version of the song, which took me a tragically long time to locate. And you know what else? I love that entire section from "'cause it's my birthday" at 1:42 straight through to the end, because the pianist starts letting this unnecessarily rocking solo loose and all of the comparatively tame background elements suddenly tighten into this jam that you couldn't pay me not to enjoy. Granted, after two or three listens, I can start to see why this might drive some parents up the walls, but there's a reason this two-minute tune keeps resurfacing in my brain decades after I first heard it. I know I intellectualize a lot of my enjoyment on this blog, which I think can be a blessing and a curse, but in the end, not everything's that complicated. Sometimes, someone just poured all of their God-given talent into writing kids' songs, and we're all the better for it. "This Hat" is today's reminder that we enjoy what we enjoy, no matter what ornate justifications we may spin.

THE BUG COLLECTOR | Haley Heynderickx I've had the adjective "forlorn" locked and loaded for weeks now, slipping it into sentences where it doesn't quite belong, because I've been waiting all that time to describe the tearful tenderness of "The Bug Collector." I clung on to it because it wasn't even my descriptor, nor was it my song—I have my wonderful girlfriend to thank for both. She remains unnamed because, you know, this is the internet, but her music shines through on so many of these posts that I think it's probably recognizable what she's picked and what I have without me ever mentioning it. Of all the sparse and soulful folk she's shared with me, though, I think this one reminds me the most of her, with everything from the album title "I Need to Start a Garden" to its poeticism in the little things, deliberate without prudence. The concept of the song, like its instrumentation, seems simple enough—the titular bug collector tries their best to scoop away their loved one's infestation of little fears, pests with a big presence, to help them see the greater beauty outside of it all. Already, I'm very touched by this, mostly because I'm so lucky to be loved like this and to feel love like this right back, but the way in which it's expressed adds an extra layer of tangible domesticity, memory, and an emotional tether that can only come with years of connection. Like a cozy watercolor in greens and browns, each bug comes to life with a paranoid anthropomorphization I never thought I'd find outside of my own skull. "And there's a praying mantis / prancing on your bathtub / And you swear it's a priest / from a past life out to getcha" feels vivid, empathetic, and neurotic all at once, cramming so much characterization into a creature whose nerve bundle barely qualifies as a brain. The Mantis's instrumentation, too, defies normal insectile scale, trading the centipede and millipede's scuttling shakers out for a—here it comes—forlorn french horn, so melancholically voluminous despite speaking for three inches of insect. This won't be the last time this week we'll discuss unorthodox sounds associated with underfoot organisms, but suffice to say, the contrast here is so vast that I almost wonder if the horn is meant to characterize not the praying mantis, but what's hiding behind it: "And I digress / 'cause I must make you the perfect evening / I try my best / To put the priest inside a jam jar." Even Haley Heynderickx's vocals, which I've since come around to, suggest this same comforting scale—a depth you can feel pressing against your cheek. I think this is what brings me back to my girlfriend the most—I get so caught up with the small and angry knots in things that seem so much bigger when they're flashing red and pincers, but she's helped me remember how much bigger and more beautiful the unfocused background can be. She treats little fears like the bug collector here, not stamping them out but scooping them aside with the compassion to ease them into untangling themselves. Even now, in the dead of winter, when the old snow gets ugly-slick and the sky turns a stark, sterile white, I can hear "The Bug Collector," and hear my girlfriend behind it, telling me where the beautiful things are.

FUNGAL CITY | Björk (feat. serpentwithfeet) Alright, before I say anything else, I'm just gonna get this out there: if you're interested in getting into Björk, do NOT start with "Fungal City," or any of her latest album, Fossora. I'm honestly still uncertain what I thought of Fossora in its entirety after almost three full listens, which might come as a surprise given my outpouring of Björk admiration last year. I have enough larval thoughts squelching around for a full album review, but since I don't have all that much time (and what I do have I can't seem to use well), the next two to four songs I end up talking about from Fossora will have to serve as one cobbled-together review in conjunction. Much like the mycology that it draws inspiration from, Fossora is pretty impenetrable, even compared to much of Björk's weirder discography. While so many little details sparked enjoyment in me, nothing really caught fire until about halfway through the album, which I think I can attribute almost entirely to its consistently dissonant tempos. To be clear, I can absolutely rock with dissonance—in fact, you wouldn't have to scroll much farther on this blog to find me complimenting dissonance in other songs, like the controlled chaos of Wilco and other jam- or jazz-adjacent artists. The metronomic dissonance here, however, left me with a total lack of focus, preventing me from really unpacking any of the nuance, subtext, or even surface qualities of many songs. Since I'm far from a musicologist and certainly not a dedicated enough musician, this is one of those cases where I totally lack the background to describe what I'm hearing, so I had to return to 12tone's excellent video on Why Ben Shapiro is Wrong About Rap to fish for vocab words. While I didn't come away with any, it did help me establish a very important distinction: Björk's Fossora is not arhythmic, but instead simply out-of-synch. Though almost every layer of each song follows the same tempo, none of them are perfectly aligned, which had an incredibly dizzying and overstimulating affect on me as a listener. This aligns with Björk's podcast, where she details her intentions to unchain herself from "the christianity of 4:4 rock and roll." I can absolutely sympathize with this desire to break free from imposed artistic convention, and it's an undeniably badass quote, but the dissonance here often totally unsettles my thoughts, keeping me from sinking teeth or even feet into the emotional landscape Björk is aiming to depict. This might be totally subjective, and I understand how little I understand about the musical talent on display here, but from my homogenous-tempo experience, very little of Fossora's first half clicked with me.

"Fungal City" was one of the two songs that shifted my perspective, which is an impressive feat nine songs deep into what felt like an inscrutable album. Though it's not my favorite of the bunch, I do think it's the strongest sampler of the conceptual palette Björk appears to be playing with. Though still strongly dissonant with its construction-site percussion, the relatively tempered chaos allows some other fascinating choices to shine through, namely the instrumentation. As with "The Bug Collector," "Fungal City" characterizes mycelial networks with an unorthodox instrumental pairing. When I try to associate a noise with fungi, I'm always restricted to delicate, rustling sounds—the clicking noises corn seedlings make to navigate soil come to mind, though that's about as far off as calling the buzz of flies the sound of decay. Maybe it's my violinist bias, but I've found that most sounds meant to represent life—even life that isn't underfoot or entirely microscopic, like insects or most fungi—are represented by strings and subtler percussion, which I think evoke a closeness and fragility through their scratchy imperfections. Birds feel like an exception to this, because their vocalizations come, at least partially, from their antorbital finestra, which creates sound very similarly to horns. While a bassoon or clarinet would make perfect sense for a goose or duck, they're not what I would've chosen to represent the cat in Peter and the Wolf, and certainly not what I would've chosen to represent mycelia. In retrospect, Björk's bold usage both prominently to characterize fungi is far and away my favorite thing about Fossora—the rich sound of wind instruments excellently captures the expansive nature of mycelial networks, and these particular woodwinds still carry an earthy texture even on their high notes that the brazenness of brass could never capture. It's also so strange to hear Björk's raspy, fairy voice alongside such a different sound—it's a pairing I once again would have been too misinformed to make, but I think this, combined with the pizzicato string accents, add whispers of that imperfect magnification that woodwinds might miss. With no disrespect to the featured vocalist serpentwithfeet (an experimental musician in his own right), there's a hairspray vibrato to his voice here that doesn't quite fit, however, and feels a little too Justin Bieber Christmas Album for my liking. Okay, sorry, maybe that's rude. I know this looks a lot like a criticism sandwich, but once I talk about more from Fossora in future installments, it'll be more of... um, a compliment sandwich garnished with critique? I promise I have many more good things to say. Stay tuned.

Oh, it's back, baby: Wayne Barlowe's Expedition, the best (and only?) book of alien wildlife art out there, is now being reprinted... and I scored myself a copy. I pontificated extensively and maybe even excessively about Expeditionlast time its art was featured, so I won't repeat myself until it's time for a full review, but I thought this flirtatious bladderhorn looked a lot like another alien a little closer to home. See what I mean? I guess the beehive is back, bigger and better than ever before. I know that sounds like shade, but Björk's Fossora look never fails to put a smile on my face. There's something loosely camp about it, although not by strict Susan Sontag standards, because Björk is absolutely pulling that fit off. Even so, it doesn't have the polished, animated look of most modern Björk—like Fossora's clarinets, there's something about this that's transparently human. It's an costume that knows it's a costume, I guess, with its mushroom cap and gill folds and its morph suit, toe-forking heels. I love it from a fashion perspective and an immersive album cover perspective—it hints at a tone that, even at its most abstract, feels more human than conceptual. Anyways, both of these deserve their own separate posts, and in my dream world, they'd have them. I'm starting a new semester and a writing group, though, so I'm just going to have to stick to just this weekly post for now. See you next time, you flirtatious bladderhorns—keep looking for that hibernating beauty this winter.